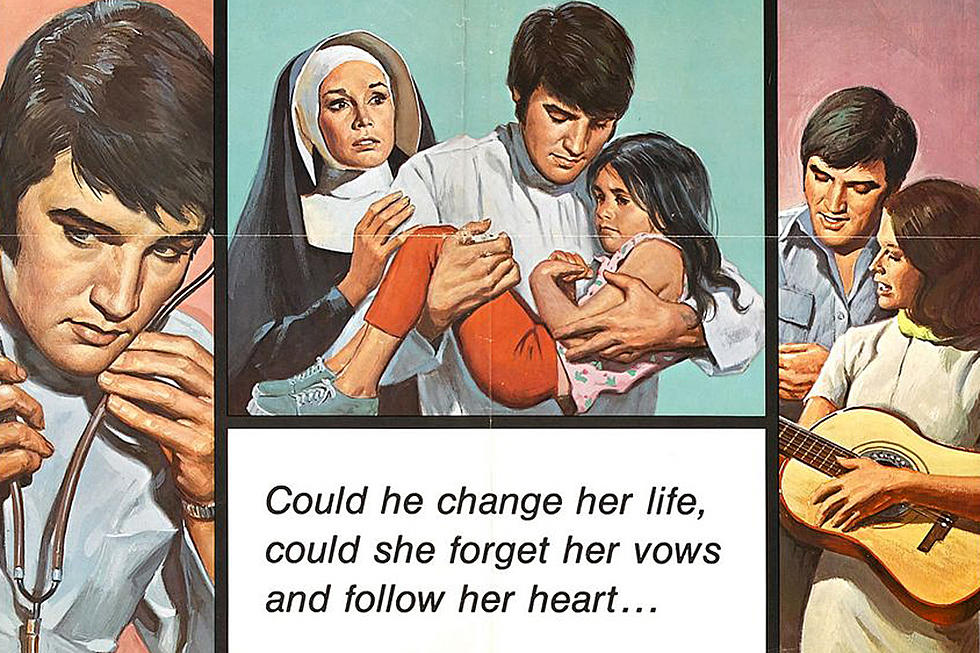

50 Years Ago: ‘Change of Habit’ Becomes Elvis Presley’s Last Film

Elvis Presley was a movie star. This is a fact that often gets lost in our memory of him, but in the 13 years between his first role in 1956's Love Me Tender and his final one in 1969's Change of Habit, he made 31 films, often churning out two or three a year.

This career move coincided with a retreat from performing, organized by his manager, Colonel Tom Parker, and it was at first a smashing success. Because of his legion of fans the movies were virtually always profitable, a rarity in Hollywood. And some of them were even good.

In 1958's King Creole, directed by Michael Curtiz of Casablanca and set in the seedy world of New Orleans nightclubs, the singer shows a good deal of acting skill in a role originally intended for James Dean. Jailhouse Rock, from 1957, highlights his languorous, smoky sexuality, and gave birth one of his most iconic songs.

Even 1964's Viva Las Vegas, in which he plays a race-car driver who takes a job as a waiter to finance his dream of driving in the Las Vegas Grand Prix, and which produced another hit song, still contains some of his youthful dangerous charm. But as the '60s wore on, his movies became more and more formulaic.

Over time, the Army veterans and singers and carnival workers and beach bums and pilots and race-car drivers all seemed to blur together into one undifferentiated character, in a mediocre movie, singing songs that were beneath his talent. By the end of the decade, this parade of schlock had taken its toll. His star was fading, in the musical arena as well as on the screen. It was during this skid that his famed 1968 comeback special arrived, rocketing him back into the limelight. It also signaled the end of his movie career as he refocused on his music; Change of Habit, released in November 1969, would be his last film.

Watch 'Change of Habit' Trailer

It's a fascinating and at times almost impossibly strange movie, one that perfectly encapsulates the collision between the '50s rock 'n' roll culture that shaped Presley and the new Age of Aquarius world he'd found himself in as he reached his mid-30s.

Presley plays John Carpenter, a doctor who works on Washington Street in a poor black and Hispanic neighborhood. Mary Tyler Moore plays Sister Michelle, one of three nuns who arrive on Washington Street, not wearing their habits, on a secret mission to help the local population. Together, Dr. Carpenter and Sister Michelle start to tackle the neighborhood problems, including underprivileged children, surly teenagers, a local loan shark and the resistance of an older out-of-touch parish priest who disapproves of the nuns' undercover operation.

Slowly, Dr. Carpenter falls in love with this Sister Michelle, not knowing, of course, that she has committed her life to God. And Sister Michelle begins to have some of the same feelings. When one of the other nuns, Sister Barbara (played by Jane Elliot), quits the order to pursue the cause of social justice, Sister Michelle begins to wonder if she might have to do the same, to pursue the cause of love. Things come to a head at a street festival where the threat of violence from the loan shark and some local toughs is only averted by Sister Michelle and her friends finally appearing in their habits. Although he beats up the loan shark and saves the day, Dr. Carpenter is terribly hurt to discover out that Sister Michelle hasn't been honest with him.

We close in a church, with Dr. Carpenter leading the congregation in a gospel song and Sister Michelle looking back and forth between him and the religious imagery on the walls, trying desperately to come to a decision about what course she will take: God or love?

What no summary can do justice to is the whipsaw effect created by this mixture of rock and roll, religion and social commentary. It features, in no particular order, a black nun (Barbara McNair) being confronted by two Black Panther-types about whether she's being true to the cause or is a race traitor; a pair of elderly women who appear at various points to give comedic commentary on the events; a group of young Latinas who learn a lesson in true femininity from Moore's nun; one of the nuns using her feminine wiles to trick some neighborhood men into moving her furniture and then is almost assaulted by them; a teenager with a terrible speech impediment who is first helped by and then attacks Moore's character; a sit-in, played for laughs, at a butcher shop that charges exorbitant prices; some extended commentary on the question of the amount of reform possible in Catholic doctrine; a brief appearance by Ed Asner (who would later star with Moore for many years on The Mary Tyler Moore Show) as a wisecracking cop; a scene in which Presley uses some kind of hippie scream-therapy to cure a kid with autism; and a closing musical number which explicitly raises the question of who's better, Elvis or Jesus.

The effect of all this is at turns charming and chaotic. The '60s are in full swing, and the filmmakers can't quite figure out what to do with them, other than to try to throw in every sequence they can dream up to show that they're hip and with it.

But throughout it all, one can't help but be reminded of the charisma and presence of the man around whom the film revolves. As absurd as many of the sequences are, Presley is always somehow both openhearted and mysterious, sexual and noble, the kind of guy one really could imagine saving the less-fortunate and convincing nuns to fall in love with him.

The King was, all the way through to the very end, the King.

The Best Rock Movie From Every Year: 1955-2018

More From 96.1 The Eagle