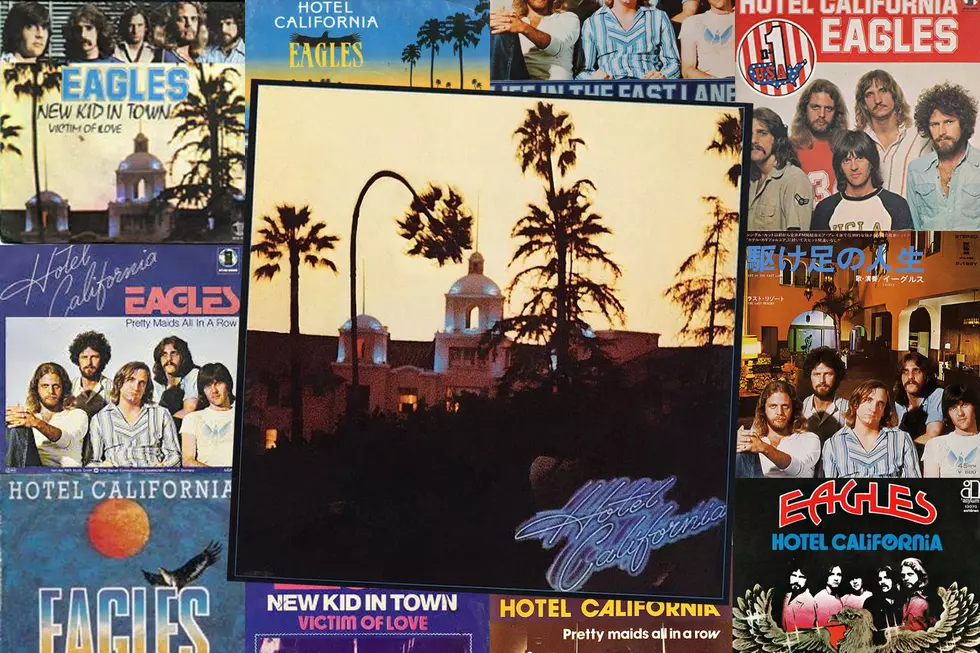

The Story Behind Every Song on Eagles’ ‘Hotel California’

The Eagles' breeziness belies their darkness; their accessibility obscures their depth. And there's no clearer example than the band's sixth LP, Hotel California, a deceptively multi-layered masterpiece that bundles cinematic rock, sleek balladry and subtle surrealism into one multi-platinum package.

Yes, the album spawned three polished singles -- "Hotel California," "Life in the Fast Lane" and "New Kid in Town" -- that have occupied radio real estate over the past four-plus decades. But these nine tracks grasped a grandeur, both sonically and lyrically, that their early forays into country-rock never foreshadowed.

"I've learned over the years that one word, 'California,' carries with it all kinds of connotations, powerful imagery, mystique, etc., that fires the imaginations of people in all corners of the globe," singer and drummer Don Henley told Rolling Stone in 2016. "There's a built-in mythology that comes with that word, an American cultural mythology that has been created by both the film and the music industry."

Hotel California has become an essential part of that mythology since its release in 1976. And it's fascinating to glance back at how this cultural lightning strike originated from a perfect storm of personnel (swapping out country-minded guitarist Bernie Leadon with blues-rock maven Joe Walsh), technology (the luxurious mid-'70s production, captured in part at Los Angeles' famed Record Plant Studios) and timing (following a steady stream of early hits, up through their 1975 greatest hits compilation, still one of the highest-selling albums ever).

Teaming again with producer Bill Szymczyk, who helmed its two previous albums, the band split time between the Record Plant and Miami's Criteria Studios -- adhering to its usual level of decadence along the way. ("Before we could even start recording, we had to scrape all the cocaine out of the mixing board," recalled Geezer Butler of Black Sabbath, who were conjuring a much heavier atmosphere at Criteria. "I think they’d left about a pound of cocaine in the board.")

Despite the distractions, the quintet (Henley, Walsh, guitarists Glenn Frey and Don Felder and bassist Randy Meisner) wound up reaching a pinnacle, both commercially and creatively: Pieces like the epic title track revealed a more artful side to their collaborative songwriting, and sales continued to swell (eventually carving out another slot on the all-time Top 5).

In the years since, Hotel California has remained Eagles' signature work. Decades later, the band is still mining the work and playing the album in its entirety. We tell the Story Behind Every Song on Eagles' 'Hotel California' below.

"Hotel California"

The centerpiece of both the album and the band's entire catalog, Hotel California's title track is six-and-a-half minutes of interwoven guitar riffs, stacked vocal harmonies and mysterious, macabre imagery. The song -- which won a Record of the Year Grammy in 1978 -- dates back to Felder's instrumental four-track demo, an intriguing 12-string jangle fleshed out with bass and drum machine. And Henley and Frey knew the song had potential to develop from that quirky first draft into something more majestic.

"Felder had submitted a cassette tape containing about half a dozen different pieces of music," Henley told Rolling Stone. "None of them moved me until I got to that one. It was a simple demo – a progression of arpeggiated guitar chords, along with some hornlike sustained note lines, all over a simple 4/4 drum-machine pattern. There may have been some Latin-style percussion in there too. I think I was driving down Benedict Canyon Drive at night, or maybe even North Crescent Drive [adjacent to the Beverly Hills Hotel] the first time I heard the piece, and I remember thinking, "This has potential; I think we can make something interesting out of this."

Felder, Henley and Frey are all credited as writers on the finished track, which the band fleshed out with a reggae-styled guitar pulse, melodic bass, booming roto-tom fills and harmonized guitar leads. But Felder's home-recorded demo loomed large over the recording session -- almost to a fault.

“Joe and I started jamming, and Don said, ‘No, no, stop! It’s not right,'” Felder told MusicRadar in 2012. “I said, ‘What do you mean it’s not right?’ And he said, ‘No, no, you’ve got to play it just like the demo.’ Only problem was, I did that demo a year earlier; I couldn’t even remember what was on it. ... We had to call my housekeeper in Malibu, who took the cassette, put it in a blaster and played it with the phone held up to the blaster. ... It was close enough to the demo to make Don happy.”

Henley told Rolling Stone the song's oft-debated lyrics -- which feature a nod to Steely Dan ("steely knives") within its winding, symbolic journey through the titular hotel -- are his finest work in that arena. "I guess I'd have to say 'Hotel California,' although I feel it important to point out that Glenn contributed some very important lines to that set of lyrics," he said. "Those lyrics employ what Glenn used to call 'the perfect ambiguity,' and are open to a wide array of interpretations – and we've seen some doozies."

"New Kid in Town"

Eagles may have shouted out Steely Dan on "Hotel California," but they conjured a bit of that band's soulful style on the laid-back "New Kid in Town." With Walsh's smooth Fender Rhodes piano and the group's parallel vocal harmonies, the song wouldn't have sounded out of place on Can't Buy a Thrill. (Notably, the song won the 1978 Grammy for Best Vocal Arrangement for Two or More Voices.)

The chorus dates back to a fragment from Eagles friend and frequent co-writer J.D. Souther, who struggled to fully flesh out the idea on his own. But, in a testament to their strengths as collaborators, Frey and Henley joined him to finish off the track together -- unifying the melodies and lyrics into a suave, seamless whole.

Lyrically, the song revolves around a gunslinger analogy, with Henley meditating on the idea that his stadium-packing band would eventually be replaced by another flavor of the month. "It's about the fleeting, fickle nature of love and romance," he reflected in the liner notes of their 2003 compilation, The Very Best Of. "It's also about the fleeting nature of fame, especially in the music business. We were basically saying, 'Look, we know we're red-hot right now, but we also know that somebody's going to come along and replace us — both in music and in love."

"Life in the Fast Lane"

Drop the needle on "Life in the Fast Line" and close your eyes. What image do you see? Probably something similar to the story that inspired the title: a non-sober Frey rollicking down the freeway at a dangerous speed. "I was riding with a guy, and we were too buzzed for our own good," he told In the Studio With Redbeard. "And he was over in the left lane in the freeway going about 85 miles an hour, and I was kinda paralyzed in the seat next to him. I said, 'Slow down, man!' He said, 'What do you mean, man? We're in the fast lane!'"

Frey hung onto the phrase for months, conceptualizing with Henley a song about "some Hollywood couple that has everything and takes it all to excess and destroys their lives." But they needed a riff to bring that tale of excess to life. Enter Walsh's signature coiling-snake guitar line.

"We were looking for input from me – Joe Walsh, rocker – that could be the foundation for an Eagles song," the guitarist told Rolling Stone. "We had a couple false starts on stuff and hadn't really found anything. But one night I was in my dressing room getting ready for a show, and I had this one lick I'd play over and over as part of warming up. Because it's really a hard lick to play. And that's "Life in the Fast Lane." And Henley came in and said, "What the hell is that?" He went and got Glenn and I played it for them. They said, "Is that yours?" And I said, "Yeah." And they said, "Well, there's our Joe Walsh Eagles song!" Don and Glenn, but mostly Don, put the words together, and Glenn kind of arranged it. And there it was. So it's a Walsh/Henley/Frey tune, and I'm really proud of it."

"Wasted Time"

Eagles pulled out all the accoutrements for this lavish break-up ballad: piano, organ, strings, phased-out guitar licks, borderline-operatic vocal harmonies. For Frey, it was an homage to the lavish production of the Philadelphia soul scene of that era.

"I loved all the records coming out of Philadelphia at that time," he wrote in the liner notes to The Very Best Of. "I sent for some sheet music so I could learn some of those songs, and I started creating my own musical ideas with that Philly influence. Don was our Teddy Pendergrass. He could stand out there all alone and just wail. We did a big Philly-type production with strings -- definitely not country rock. You're not going to find that track on a Crosby, Stills & Nash record or Beach Boys record. Don's singing abilities stretched so many of our boundaries. He could sing the phone book. It didn't matter."

Henley, the song's co-writer, aimed for a much more direct lyric than, say, the shadowy metaphors of "Hotel California." "Nothing inspires or catalyzes a great ballad like a failed relationship," he told Rolling Stone. "Still, it's a very empathetic song, I think."

"Wasted Time (Reprise)"

This brief instrumental coda opened the original vinyl's second side with a flourish of symphonic sweetness. The string arrangement is credited to Jim Ed Norman, one of Henley's former college friends and the keyboardist in the singer's pre-Eagles band Shiloh. Norman, who eventually became president of Warner Bros. Records Nashville, even joined in on the band's Hotel California tour, conducting a 46-piece orchestra and 22-member choir onstage.

"Victim of Love"

On Hotel California, Eagles boasted five legitimate songwriters -- a breadth of attack reflected in the album's diversity. The original plan, said Felder, was to showcase each member behind the microphone, but that plan fell through during the recording of slinky blues-rocker "Victim of Love."

The guitarist recorded several attempts at a lead vocal, but none crossed the band's dauntingly high threshold. While Felder was out to dinner with band manager Irving Azoff, Henley stepped in and recorded his own take. "It was great," Felder told UCR of the drummer's vocal. "He was fantastic. But I was really upset because we were supposed to — everybody have a song on that record. … I was told that I was going to be able to sing that."

Resentment lingered beyond the session. “Don Felder, for all of his talents as a guitar player, was not a singer,” Frey bluntly noted in the band’s 2013 documentary, The History of the Eagles. Henley added that Felder's vocals “simply did not come up to band standards."

"Pretty Maids All in a Row"

Walsh's signature Hotel California moment may be the tricky lick on "Life in the Fast Line," but he shows a more vulnerable side on this slow, oceanic waltz. He crafted the track with singer-songwriter (and former Barnstorm bandmate) Joe Vitale, who wound up joining Eagles as a touring member.

"To make the Eagles really valid as a band, it was important that we co-write things and share things," Walsh recalled in 1983. "'Pretty Maids' is kind of a melancholy reflection on my life so far, and I think we tried to represent it as a statement that would be valid for people from our generation on life so far. Heroes, they come and go. ... Henley and Frey really thought that it was a good song, and meaningful, and helped me a lot in putting it together. I think the best thing to say is that it's a kind of melancholy observation on life that we hoped would be a valid statement for people from our generation."

"Try and Love Again"

Meisner guided the band back to country-rock with this swooning deep cut, belting over acoustic strums, melodic guitar harmonies and his own melancholy bass line. The song became his swan song in the band he co-founded: He quit the lineup in September 1977, following the Hotel California tour, after struggling with health problems and band tension.

"Try and Love Again" is rarely mentioned in the same breath as classics like "Hotel California" and "Life in the Fast Lane," but its twang and atmosphere add another color to the album's palette. And though it was performed only a handful of times in its day, the song enjoyed a renewed spotlight on the full-LP tour.

"The Last Resort"

Hotel California dims its neon lights with this maximalist protest anthem against man's endless thirst for empty conquest. Over seven-and-a-half minutes, Henley surveys an America squandering its resources and torching its core values -- a message informed by the band's reach into environmental and social issues. "We satisfy our endless needs and justify our bloody deeds," he sings, "in the name of destiny and in the name of God."

"The gist of the song was that when we find something good, we destroy it by our presence — by the very fact that man is the only animal on earth that is capable of destroying his environment," the singer told Rolling Stone in 1978. "The environment is the reason I got into politics: to try to do something about what I saw as the complete destruction of most of the resources that we have left. We have mortgaged our future for gain and greed."

Frey, who co-wrote the song, reflected years later that "The Last Resort" was Henley's attempt at an "epic."

"We were very much at that time concerned about the environment," he told In the Studio With Redbeard. "We were starting to do anti-nuclear benefits. It seemed to be the perfect way to conclude and wrap up all the different topics and things we'd explored on the Hotel California album. I think Don really found himself as a lyricist on that song — really kind of outdid himself."

Top 10 Reunion Tours

The Complicated History of the Eagles’ ‘Victim of Love’

More From 96.1 The Eagle