The Story of Paul McCartney’s Controversial ‘Give Ireland Back to the Irish’

Paul McCartney reacted to a horrific event by writing and releasing “Give Ireland Back to the Irish” in February 1972. It seemed to be an act of honesty, but was there more to it?

British soldiers had just shot 26 unarmed civilians on Jan. 30 in Derry, Northern Ireland, killing 13 on the scene. The incident, an extension of politico-religious tensions reaching back to the 17th century, became known as "Bloody Sunday" – tragically, the fourth violent event relating to Anglo-Irish relations to be given the name.

Images from the scene, including that of Father Edward Daly waving a blood-stained handkerchief for a white flag as friends carried a dying man to safety, provoked horror and anger across the world. And in London’s Abbey Road Studios, it provoked Paul McCartney into an action that could have put his fledgling post-Beatles career on the line.

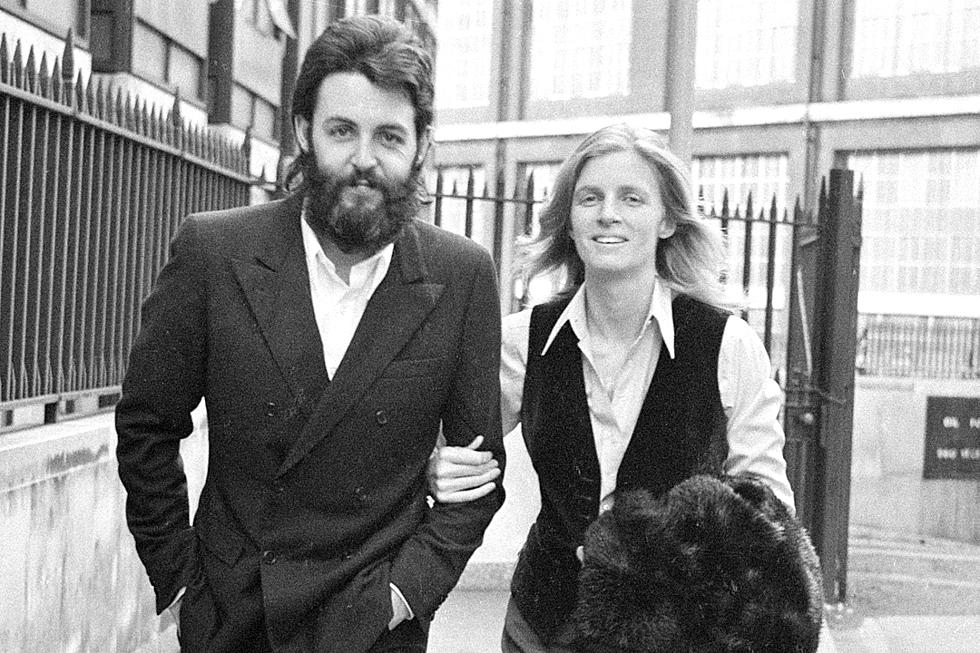

His song “Give Ireland Back to the Irish” was written the next day, with assistance from wife Linda, then recorded by his band Wings the day after, and released four weeks later. Musically, it’s hardly groundbreaking. It might even pass for a pub-rock band ditty, if it wasn’t for some of those impossible-to-ignore sparks of brilliance that demonstrate genius at work.

But that wasn’t the point. The point was that Paul McCartney was at the right place at the right time to be proactive about the horror, while many others could only feel helpless. His parents were of Irish origin and his home city, Liverpool, was a port center less than 140 miles from Dublin. He reflected in 2016: “Half of Liverpool comes from Ireland. That was the shocking thing: It felt like we were fighting us, and that we’d killed them, and it was all very visibly on the news.”

Wings, formed in 1971 by McCartney and Linda, also included guitarist Denny Laine, drummer Denny Seiwell and Northern Irish guitarist Henry McCullough. They all agreed the song was worth recording and releasing – and they were ready for the backlash, which began almost immediately.

Listen to Paul McCartney Perform 'Give Ireland Back to the Irish'

“I wrote ‘Give Ireland Back to the Irish,’ we recorded it and I was promptly phoned by the chairman of EMI, explaining that they wouldn’t release it," McCartney recalled in his 2002 memoir Wingspan. "He thought it was too inflammatory."

As a former Beatle, he has was able to press the point, and so the label boss relented. “He said, ‘Well, it’ll be banned,'" McCartney added. "And of course, it was."

Broadcasting authorities in the U.K. issued a blanket ban across TV and radio. Even the popular non-regulated station Radio Luxembourg refused to play it. When it was mentioned in the singles chart it was simply referred to as “a record by the group Wings.” McCartney tried to buy airtime on British commercial TV but regulators refused to permit it. Nevertheless, it did chart – reaching No. 16 in Britain, No. 21 in the U.S. and No. 1 in the Republic of Ireland and Spain.

McCartney, whose work reflects a belief in popular art reflecting life, maintained that it had to be done. “‘Give Ireland Back to the Irish’ wasn’t an easy route, but it just seemed to be the time,” McCartney said. “It was the first time people questioned what we were doing in Ireland.”

By making a stand, Wings could have easily put themselves in the firing line – literally. Indeed, McCullough’s brother was assaulted in Northern Ireland as a result of the guitarist’s involvement and, of course, McCartney lost the support of those who didn’t agree with his position.

BBC commentator Stuart Maconie said in 2013 that the non-album track had been worthwhile. “Like many people he was horrified by Bloody Sunday, and as a child of the Irish diaspora in the north west of England, he felt it even more keenly. I think he was utterly sincere and it was a very brave move.”

He also rejected the idea that McCartney was just trying to continue his competitive relationship with former bandmate John Lennon, who’d previously taken part in a New York protest against the British Army’s actions in Northern Ireland. (Lennon released two songs on the subject later in 1972, “Sunday Bloody Sunday” and “Luck of the Irish,” but neither achieved any notoriety.)

Northern Irish journalist Eamonn McCann, however, felt the single was too convenient. “The cause has floated in and out of the ‘trendy left,’” he said. “The issue was quite an easy one to get involved with.”

Irish music journalist Stuart Baillie argued that the only remarkable thing about the song was its broadcast block: “The ban gave it more kudos – in my opinion it was a poor song with weak lyrics. It’s arguably McCartney’s most banal song.”

Another three decades were to pass before the violence came to an end, in the aftermath of a peace process that became increasingly high-profile in the '90s. While the release of a quickly-written pop single so many years earlier might seem relatively insignificant, it can also be seen as one of those many small events that lead up to great changes.

McCartney admitted at the time that he wasn’t overtly political and didn’t intend to make a habit of it. It seems fair to take him at his word that it was a knee-jerk reaction to a horrifying moment. But he didn’t learn nothing from the global effect generated by the Beatles, and he’d have known that he, of all people, was in a position to do something that others couldn’t do.

The fact that it’s not a strong song, and the speed of its production, would at least lend credence to the suggestion that it was an act of honesty. On the other hand, Wings’ 1971 debut album Wild Life had also been put together quickly, because McCartney felt it was a good way to capture spontaneity – so it could just have been his modus operandi of the time.

Still, if he did have other motivations such as competing with Lennon or trying to engineer controversy, they’re surely mitigated by that underlying honesty.

Paul McCartney Released One of Rock's Most Hated Records

See Paul McCartney in Rock’s Craziest Conspiracy Theories

More From 96.1 The Eagle